A sermon for Advent 2

Mark 1: 1-8

I wonder if you can think back to a time when you were lost, really lost. That sense of wandering around alone waiting to be found.

It might be a time as a child when you lost your parents in a supermarket; on a hiking trip when your map reading skills failed you, or stuck in a strange city with no data left on your phone so you can’t use google maps.

I remember being lost in Clapham Common in the days before mobile phones. I was 19, at that time I didn’t know London at all but had gone to see a friend. I was early so I stopped off to go for a walk in the common. I parked my car, spent an hour or so walking around and enjoying the afternoon, and then I went back to my car.

I had no car keys. I’d dropped them somewhere, and my wallet was locked in the car. I had no money, and was alone in a city I didn’t know. The sun was going down.

I retraced my steps. Nothing. I searched high and low. Nothing. I wandered round and round in circles and eventually sat down in the middle of the park, in the dark, and cried.

Wildernesses come in all shapes and sizes. Not many of us have experienced a physical wilderness, or true desert. Clapham Common is hardly a wilderness! But we do know what wilderness feels like. That sense of being lost, out of control in the unknown, of being without bearings.

Wilderness is an uncomfortable place.

Mark’s gospel opens dramatically in the literal wilderness with John the Baptist appearing as if out of nowhere, looking wild with his camel-hair clothing and honey and locust diet.

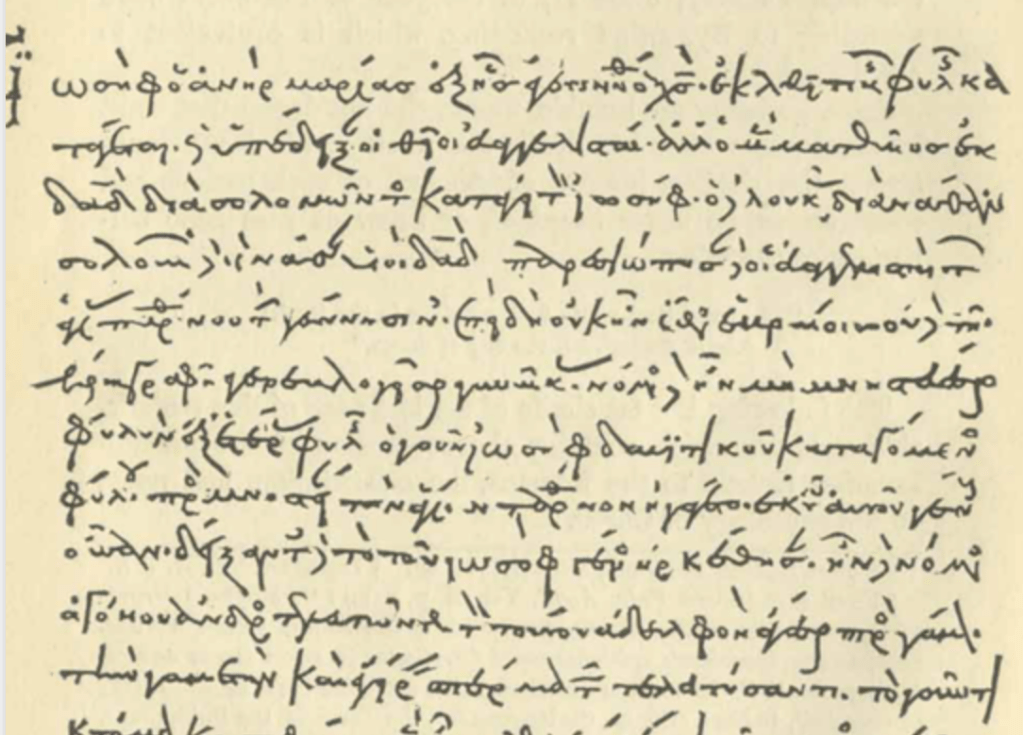

The gospel begins with words from prophets Malachi and Isaiah:

The voice of one crying out in the wilderness:

Mark 1.3

“Prepare the way of the Lord,

make his path straight.”

There had been prophetic silence for around four hundred years before this moment when John the Baptist bursts onto the scene. The last prophetic voice recorded in the Hebrew bible had been that of Elijah’s in the book of Malachi and since then, pretty much nothing.

And throughout that wilderness time of silence God’s people were waiting for the one they’d be promised, who would free them from oppression: The Messiah.

In the Bible, time in the wilderness isn’t to be feared; it’s a place of learning, transformation, and growth.

In Scripture we see over and over again of God’s people being led into the desert or wilderness in order to be taught something important. We remember Moses and Miriam leading the Israelites through the wilderness years as they learn to trust God’s provision; Hagar who hears God’s voice whilst sitting in desert in despair; Elijah, who is led into the wilderness before hearing God’s still small voice in the silence. And of course Jesus himself is led there after his baptism.

And so it’s from wilderness that John bursts onto the scene proclaiming Good News.

Someone is coming who is greater than I

Get ready for him

Turn around and make a path for him

Back to my story in Clapham Common

It was dark, I was vulnerable and alone. I had a very new Christian faith and realised I needed at this time, in that place, to exercise it.

So I sent up a quick ‘God, what do I do now’ prayer. And I had the strongest sense that what I needed to do was to get on my knees and pray. So, in the middle of the park, in the dark, I got on my knees and prayed. And as I did so I knew without a shadow of a doubt that my keys had been found. I knew it was going to be OK. And what I needed to do was to turn around and go back to the car.

So I walked back to the car and as I did so I saw a man walking towards me calling out to me: ‘Excuse me, Miss, are these your keys’?

He’d seen me wandering around from the upper window of nearby flat, had come down from his home, and had searched around the undergrowth, and found the keys.

And in doing so had not only given me the means to get home, but also strengthened my faith at a time when I really needed it, and for years to come.

Advent is a time when we recognise our lost-ness, that we can’t find the way on our own, that we so often wander round and round in circles not quite knowing where we are heading.

In the biblical wilderness people are never left there for ever. They are called from the wilderness into something far better – into deeper faith, clearer vision, stronger resolve.

God, the creator of all, didn’t remain silent, and doesn’t just watch us wandering around from his high tower. Instead he came amongst us, as one of us, in the form of a child, to enter into our lostness and to show us the way through the dark. This is the Good News of Jesus Christ that Mark proclaims in his gospel.

Jesus was ‘God with us’ (Emmanuel) in human form for a while, and remains with us through his Holy Spirit until the time when he will return. And John the Baptist, like Elijah before him, and Isaiah before him encourage us to prepare the way for him.

God is with us, and is coming to be with us. How do we make a clear path for him? That is the task for Advent.

Repent. Stay awake. Clear out the obstacles which get in the way.

If you are in a wilderness stage of life, feeling like you are wandering around in circles, you are not alone. Perhaps we are invited to welcome the wilderness, to hear what God may be saying to us within it, or to listen to how God might be guiding us through it. God doesn’t always sent an immediate answer to prayer in the way that happened to me on Clapham Common – in fact I don’t think I’ve experienced anything quite as clear since then. But it sustains me nonetheless.

And so, this Advent, let us prepare the way to welcome Jesus, perhaps by getting on our knees to pray (maybe not in the dark in a park!), being prepared to sit in silence, by turning around…

and by being willing to be found.

Amen