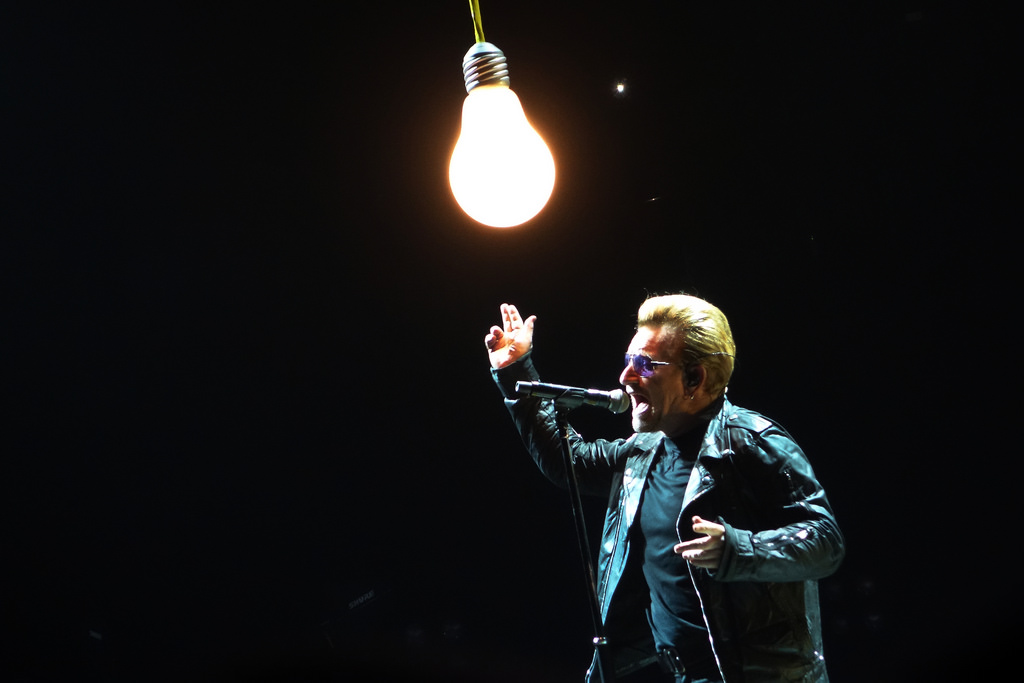

Image source: The adoration of the shepherds, Rembrandt

Adaption of a sermon by Barbara Brown Taylor

I came across this narrative sermon by Barbara Brown Taylor and loved it so much I thought I’d share it with you on this Christmas morning.

Once upon a time—or before time, actually, before there were clocks or calendars or Christmas trees—God was all there was. No one knows anything about that time because no one was there to know it, but somewhere in the middle of that time before time, God decided to make a world. Maybe God was bored or maybe God was lonely or maybe God just liked to make things and thought it was time to try something big.

Whatever the reason, God made a world—this world—and filled it with the most astonishing things: with humpback whales that sing and white-striped skunks that stink and birds with more colours on them than a box of Crayola crayons. The list is way too long to go into here, but suffice it to say that at the end when God stood back and looked at it all, God was pleased. Only something was missing. God could not think what it was at first, but slowly God became aware of what it was.

Everything God had made was interesting and gorgeous and it all fit together really well, only there was nothing in the world that looked like God, exactly. It was as if God had painted this huge masterpiece and then forgotten to sign it, so then got busy making a signature piece, something made in God’s own image, so that anyone who looked at it would know who the artist was.

God had one single thing in mind at first, but as God worked, realized that one thing all by itself was not the kind of statement that God wanted to make. God knew what it was like to be alone, and now that God had made a world, knew what it was like to have company, and company was definitely better. So God decided to make two things instead of one, which were alike but different, and both were reflections of God—partners who could keep God and each other company.

Flesh was what God made them out of—flesh and blood—a wonderful medium, extremely flexible and warm to the touch. Since God, strictly speaking, was not made of anything at all, but was pure mind, pure spirit, God was very taken with flesh and blood. Watching these two creatures stretch and yawn, laugh and run, God found with surprise feelings of envy. God had made them, it was true, and knew how fragile they were, but their very vulnerability made them more touching, somehow. It was not long before God was found falling in love with them. God liked being with them better than any of the other creatures God had made, and God especially liked walking with them in the garden in the cool of the evening.

It almost broke God’s heart when they got together behind God’s back, and did the one thing they had been asked not to do, and then they hid— Hid from God!—Hid while God searched the garden until way past dark, calling their names over and over again.

Things were different after that. God still loved the human creatures best of all, but the attraction was not mutual. Birds were crazy about God, especially ruby-throated hummingbirds. Dolphins and rabbits could not get enough of God, but human beings had other things on their minds. They were busy learning how to make things, grow things, buy things, sell things, and the more they learned to do for themselves, the less they depended on God. Night after night God threw pebbles at their windows, inviting them to go for a walk, but they said they were sorry, they were busy.

It was not long before most human beings forgot all about God. They called themselves “self-made” men and women, as if that were a plus and not a minus. They honestly believed they had created themselves, and they liked the result so much that the divided themselves into groups of people who looked, thought, and talked alike. Those who still believed in God drew pictures of God that looked just like them, and that made it easier for them to turn away from the people who were different. You would not believe the trouble this got them into: everything from armed warfare to cities split right down the middle, with one kind of people living on that side of the line and another kind on the other.

God would have put a stop to it all right there, except for one thing. When God had made human beings, they were made free. That was built into them just like their hearts and brains were, and even God could not take it back without killing them. So God left them free, and it almost killed God to see what they were doing to each other.

God shouted to them from the sidelines, using every means available, including floods, famines, messengers, and manna. God got inside people’s dreams, and if that did not work, woke them up in the middle of the night with whispering. No matter what God tried however, God came up against the barriers of flesh and blood. They were made of it and God was not, which made translation difficult. God would say, “Please stop before you destroy yourselves!” but all they could hear was thunder. God would say, “I love you as much now as the day I made you,” but all they could hear was a loon calling across the water.

Babies were the exception to this sad state of affairs. While their parents were all but deaf to God’s messages, babies did not have any trouble hearing God at all. They were all the time laughing at God’s jokes or crying with God when God cried, which went right over their parent’s heads. “Colic” the grown-ups would say, or “Isn’t she cute? She’s laughing at the dust mites in the sunlight.” Only she wasn’t, of course. She was laughing because God had just told her it was cleaning day in heaven, and that what she saw were the fallen stars the angels were shaking from their feather dusters.

Babies did not go to war. They never made hate speeches or littered or refused to play with each other because they belonged to different political parties. They depended on other people for everything necessary to their lives and a phrase like “self-made babies” would have made then laugh until their bellies hurt. While no one asked their opinions about anything that mattered (which would have been the smart thing to do), almost everyone seemed to love them, and that gave God an idea.

Why not create God’s self as one of these delightful creatures? God tried the idea out on the cabinet of archangels and at first they were very quiet. Finally the senior archangel stepped forward to speak for all of them. He told God how much they would worry, if God did that. God would be at the mercy of God’s creatures, the angel said. People would be able to do anything they wanted. And if God seriously meant to become one of them there would be no escape if things turned sour. Could God at least become like them as a magical baby with special powers? It would not take much—just the power to become invisible, maybe, or the power to hurl bolts of lightning if the need arose. The baby idea was a stroke of genius, the angel said, it really was, but it lacked the adequate safety features.

God thanked the archangels for their concern but said no, thought it best just to be a regular baby. How else could God gain the trust of creation? How else could they be persuaded that God knew their lives inside out, unless God lived one like theirs? There was a risk. God knew that. Okay, there was a high risk, but that was part of what God wanted them to know: that God was willing to risk everything to get close to them, in hopes that they might love their creator again.

It was a daring plan, but once the angels saw that God was dead set on it, they broke into applause—not the uproarious kind but the steady kind that goes on and on when you have witnessed something you know you will never see again.

While they were still clapping, God turned around and left the cabinet chamber, shedding robes on the way. The angels watched as the midnight blue mantle fell to the floor, so that all the stars on it collapsed in a heap. Then a strange thing happened. Where the robes had fallen, the floor melted and opened up to reveal a scrubby brown pasture. Speckled with sheep—and right in the middle of them—a bunch of shepherds sitting around a camp-fire drinking wine out of a skin. It was hard to say who was more startled the shepherds or the angels, but as the shepherds looked up at them, the angels pushed their senior member to the edge of the hole. Looking down at the human beings who were all trying to hide behind each other (poor things, no wings), the angel said in as gentle a voice as he could muster,

“Do not be afraid; for see—I am bringing you good news of great joy for all the people: to you is born this day in the city of David a saviour, who is the Messiah, the Lord.”

And away up the hill, from the direction of town, came the sound of a newborn baby’s cry.

From Bread of Angels, Barbara Brown Taylor, Canterbury Press